Figure 4: Raphael, Villa Madama, Loggia, begun c. 1516, Rome

However, again one can revert to the Italian sixteenth century and this time to its paintings. Of Giulio Romano, Frederick Hartt speaks of his use of the lattice (the grid rotated through an angle of 45°) which is expandable or contractible at will; and, in this context, one may also think of other pictorial grids (just possibly manifested by Rosso Fiorentino and Bronzino) organized more strictly in terms of a series of horizontal and vertical coordinates. The foregoing remarks related to architecture and painting are introduced in order to illustrate the original sources of my interest in sixteenth century manifestations.

It is not supposed that gridding, strapping, quadratura, etc., are the sole, or even the most important, component of sixteenth century painting and architecture; and it is certainly not supposed that sixteenth and twentieth century styles are, in any way, directly commensurate. Indeed, while in the twentieth century, one might believe that the simultaneous existence of architectural and pictorial grids has been largely accidental, that—with the exception of Le Corbusier (Figure 6)—their relationship has been mostly haphazard, pragmatic, and diffuse, then—and conversely—in the sixteenth century one might equally suppose that the condition and interrelation of the two grids was far more provocative, intellectualistic, and extreme.

For the region in which painting and architecture intersect, so far as I am concerned, must always be among the most pregnant and least- considered areas of consideration. Painting and architecture are equipped with different missions. The role of painting is to present the illusion of three dimensions in the reality of two; and the role of architecture might possibly—though one can scarcely say it—be the opposite: to simulate the existence of two dimensions in the reality of three.2

Or such, I suppose, many of the great architectural masters of the sixteenth century unconsciously perceived their purpose to be—to flatten, to layer, to stratify, to reduce architectural incident to the condition of bas-relief, and to promote lateral spread at the expense of perspective depth. And again to introduce Frederick Hartt on Giulio, the presence of these activities promotes a subversion of “the visual cone of Renaissance perspective (which) implies the spatial existence of every form and its spatial relationship to every other form”3—a subversion which is prone to place emphasis upon planarity. By way of comparison, one needs only to look at Giulio Romano’s Battle of Constantine (Figure 7) and Raphael’s School of Athens (Figure 8), both in the Rooms of Raphael in the Vatican, to emphasize the obvious.

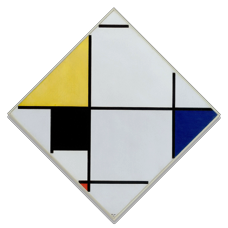

Figure 5a: Piet Mondrian, Lozenge Composition with Yellow, Black, Blue, Red, and Gray, 1921

Page 2

Figure 6: Le Corbusier, detail, High Court Building, Chandigarh, India

(Click title to return to first page)

Figure 5b Piet Mondrian, Composition with Blue and Yellow, 1935